In the boss fights of South Of Midnight, you’ve got to find a pulsing wound on the body of the monster and strike it to cleanse the giant beast of its “stigma”. In truth, these creatures are analogues for human characters, sometimes people who have literally transformed into beasts, afflicted by a thorny curse that drives them into frightening states of rage or panic. This is a game about festering trauma – history as a painful wound you’ve got to poke in order to eventually heal. Strip back the scales and feathers of folk allegory and these are human tales of shame, hunger, neglect, and abuse, some more effective than others. It’s a gorgeous game with a killer approach to music, if sometimes hobbled by the ropey trappings of its action adventure genre.

You play Hazel, a track runner of the US south. A hurricane is coming and she’s packing up her family’s belongings to escape. But her home is soon washed away in the storm, with her mother inside, and Hazel sets off to find it, discovering along the way that she has the magical powers of a “weaver” – someone who can mend the corruptive stigma that is growing in harsh brambles around the swamps and forests of her homeland. Of course, this is an action game, so those same powers also let her batter shadowy “haints” who appear with claws and fists and bloated flies to fight her.

Watch on YouTube

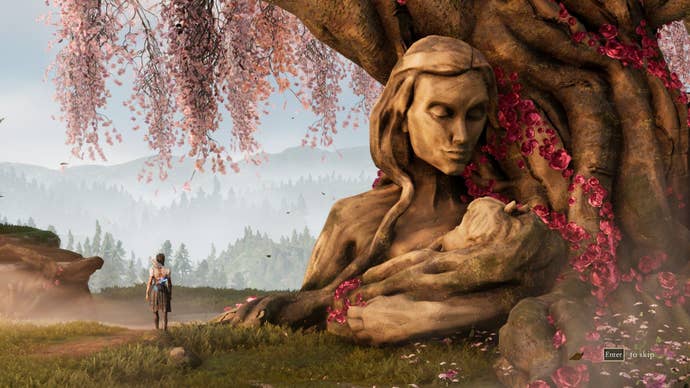

It’s a game of glamorous good looks. Humans with deep, expressive faces and fanciful costumes meet giant catfish with ornate whiskers and glittering eyeballs. Foxes and rabbits scurry about as you run through the foresty corridors, herons take off handsomely into the sky, dragonflies buzz, alligator snapping turtles grunt by the water’s edge. A stop motion effect heavily advertised in trailers doesn’t feel as transformative as it might in the animated Spider-Man movies, mostly because it’s not applied to the game in a truly consistent way, and even a bit of hanging can make it look like your graphics card is having framerate issues instead of it being an intentional style choice. But even putting that visual gimmick aside, it’s still an often stunning thing to look at.

It’s also sonically off the charts. There are brief haunting hymns that sound with every use of your weaver abilities – double jumps and dashes have rarely sounded so good – and most chapters feature a musical number that rises from choral chants to a full-blown folk song as you discover more about the characters involved in whatever folk story you’re currently fight-healing your way through. Honestly, the music and sound design here will probably win awards, if the people in charge of such things have any ounce of taste.

You might sense a “but” coming. You’re right. The sights and sounds, and its stylish sense of magic, are enough to recommend it. But my hands aren’t half as impressed as my eyes and ears with what is otherwise a very plain third-person action adventure. The imaginative approach to character design, musical score, and narrative theme isn’t matched by the actions you’ll be performing throughout the game, which are mostly an undemanding collection of third-person runalong mainstays.

The Uncharted-style wall clambering feels particularly dated, as does the squeezing through small gaps, the obvious combat arenas, the overlong Prince Of Persia style escape sequences, the straightforward box-pushing puzzles… It’s far from the only game guilty of following in well-worn footsteps, but I still spent a lot of time with South Of Midnight feeling that, for all its visual and aural splendour, I’ve seen a lot of this done before and done better. It’s a game that is eye-catching and, importantly, deeply emotionally literate, yet I found it unambitious and undemanding in a lot of its step-by-step movements.

There’s also a feeling like it has little trust in you as a player, such as when it wrests the camera from you to focus on something in the distance, or snaps throwable objects straight to destructible hazards instead of letting you aim yourself. It sometimes has the same dearth of trust in you as a reader, in moments where it spells things out in bold or explains the entire level you’ve just played in loading screen storytime sequences (to be fair, these are skippable).

Hazel also loves talking to herself in that protagonist-with-no-filter kind of way, pointing out solutions and next steps before you’ve even had an opportunity to look around. “You can squeeze into small spaces I can’t!” she exclaims when meeting a small companion who will become a usable skill. It’s as if Hazel is a player too, and has access to the game design document. There are lots more of these distracting “player direction” lines of dialogue muddying otherwise compelling chats between characters. Every moment when this puppet companion needs to be used, the instructions will flash on screen anyway, further proof that the game wants to shepherd you through its world rather than let you explore it on your own terms.

Combat can also feel a little stiff. It’s mostly a case of locking onto an enemy and slashing them with your weaving tools, then dodging away just as they strike to deliver a big blast of energy that stuns them. But that dodge can feel a little sticky and unresponsive, probably since you can only dodge-cancel out of certain moves. You get special attacks that yank an enemy closer, or push them away, but the relatively long cooldowns for these powers mean that you can’t use these more satisfying tactics more than a few times each fight, at least until you unlock the means to quicken said cooldowns.

I have other fighty nitpicks. Hazel’s recovery time after being knocked down often feels painfully slow, the gossamer swishes of enemy attacks can make busier brawls unclear, and I wish you could lock onto an enemy sooner as they spawn in, instead of waiting for them to fully materialise. As video game smash ‘n’ slash combat goes, it’s serviceable but stodgy and, as with much of the game, it becomes repetitious in a way that could be cured if there was simply less of it. And as meaningful as it is to have each boss’ trauma manifest as a specific wound, I found the process of actually fighting those bosses a plainly patterned going-through-of-the-motions.

And this is all housed within a repetitive structure that reoccurs every chapter. You enter a level, cleanse roughly four arenas of enemies, do an escape sequence from a fog chasing you, then (sometimes) fight a boss. Chapters rarely deviate from that rhythm, and the sense of repetition is worsened by heavy use of exploding mushrooms and urchin-like expando-thorns that litter the levels, both of which are employed in abundance, almost right up until the end of the game. South Of Midnight is by no means long, at 10-15 hours to complete, yet I felt much of it could be safely cut away to result in a leaner game. For me, its repeating hazards and patterns of storytelling started to feel overworked by the halfway point.

That’s a lot of my curmudgeonly muttering out of the way. None of the above concerns may matter to anyone who wants to stick it onto story mode and play a chapter every night like they’re indulging an episode of a TV show about giant spiders with a taste for townsfolk. As I often point out, having to rinse through a game for review warps your perception of its pacing somewhat. I’m glad to report one important thing didn’t buckle under that pressure: the strength of its main character.

Hazel is simply a decent human. She’s down to earth but knowledgeable about the history of her homeland, its roots as a sugar cane plantation, and the tremors of slavery that still linger (sometimes as literal ghosts) in the forgotten ruins she stumbles upon. Her track runner attitude and demeanour manifest in some fun ways, as when she stretches her hamstrings after a fight, or shakes off her legs when idle. She is mouthy yet refreshingly non-judgmental. She makes plenty of jibes at rich folk but when faced with flashes of other people’s backstory (a swamp man’s past or her own granny’s troubled era of motherhood) she displays sincere understanding and empathy. Her warmth extends even to people who’ve done awful things. There’s something comforting about controlling a person this open-hearted. Even murder, neglect, and betrayal do not ruffle her feathers, and her emotions only truly boil over when it comes to the health of her own mother.

Granted, sometimes that empathic tale and the game’s platformy action feel at odds. Moments of tonal whiplash between story and action, as exemplified when one particularly dark flashback of a childhood trauma is immediately followed by a Crash Bandicoot chase across thorny platforms. It’s not enough to completely undermine the power of the moment (another example of the cankered roots of history rotting beneath living memory) but it can be a little distracting to learn a horrible truth, then suddenly be dodging spikes to jaunty music.

Again, that feels like the result of the action adventure format. I complained earlier that the game sometimes lacks trust. But in the storytelling, at least, there is some faith in the player. It doesn’t bombard you with the inspirations behind its folk tales, for example (but you can always look them up). The quilts that you sometimes magically wallrun across are based on stories of coded blankets used in the underground railroad, a folk history it also doesn’t plain-facedly explain. And there are deeper crimes against some characters that it does not name explicitly but which it does mercifully trust you to understand.

It’s here, when the game lets these suggestions exist without overtly commenting on them, that it retains most power. As a white Irish lad, I’m not the best equipped to talk about how it handles themes of race and class in the United States, or the echoes of intergenerational trauma upon black people down through layers of US history, but if you are looking for a game which is literate in those themes – while not shying away from the clear inference that rich, white people are behind much of that reverberating pain – then know that South Of Midnight does so with a lot of confidence. Its final scenes feel like a strong cocktail of understanding and accountability, coolly served by a practiced mixologist of myth.

I will end with one thing I have loved about it: the endless use of wildlife as symbolism and set dressing alike. As I’ve said, foxes and opossums will consider you from afar and scurry away as you approach, but this isn’t always mere animatronic decoration. They will often lead you to hidden corners where you can slurp up energy to upgrade your powers. Crows are constantly used as feathery signposts to show you the right direction. In the burrowing holes that your soft toy sidekick can explore, rabbits and raccoons will silently peer at you through roots, as if through the windows of their subterranean homes, with small chairs and tables adorning these dens, like in Wes Anderson’s Fantastic Mr Fox.

Not only are animals woven into the hurt of humanity as symbolic spiders, mistreated gators, and tortured birds, but the closing shots of many chapters will see ordinary and silent forest creatures watching in quiet contemplation as Hazel drifts away on the back of her catfish friend. Towards the end of the game, these animals – the smallest unit of animated environmental storytelling – gather around Hazel in a way that signals support from a kingdom beyond her ken. It is one of the game’s quieter suggestions: we are part of a greater nature, and when that world is wounded, by storm or by human hands, we become wounded ourselves.